Gumbleton’s Narration of Hostages’ Eve inside US Embassy in Tehran

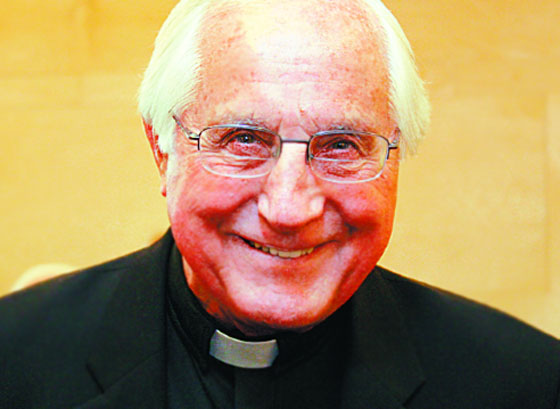

The name of Thomas J. Gumbleton, the American priest, is so linked to the happenings of the early days of the Islamic Revolution that to browse through his cultural and political activities would be impossible without taking the memories of this religious figure into account. Gumbleton is a retired Roman Catholic auxiliary bishop of the Archdiocese of Detroit who has years of work in peace-seeking movements and civil activities in his records. He is the founding President of Pax Christi, which is an organization known to be devoted to promote peace and has been active for over half a century now. During the capturing of the US Embassy in Tehran by the students, known as “Followers of the Imam’s Path” and taking the embassy staff hostage which took 444 days, Mr. Gumbleton and two other active priests in peace were invited to celebrate Christmas for the embassy staff in Tehran. After nearly 35 years since the 1979 Revolution, Mr. Gumbleton’s account from the early revolutionary days is still intriguing.

AVA Diplomatic’s Exclusive Interview with Bishop Thomas J. Gumbleton,

Fouding President of Pax Christi, a Peace-Promoting Organization

Interview by Mohammadreza Nazari

Your name is linked with the early revolution events of Iran and indubitably, restating your memories of those days can help us reiterate the events that have since shadowed the Iran-Us relations. What made you travel to Iran after the US embassy was captured in 1979?

In reality I was invited to come by the government and those who have taken control of the embassy. They invited me to come to perform Christmas religious services for the hostages. And so, I was very happy to do that along with two other ministers, Rev. Dr. Coffin and Baptist pastor Charles Gray. The three of us were invited to perform the Christmas services for the hostages. So we all said yes and your government invited us to come and we spent Christmas Eve and early Christmas morning inside the embassy, celebrating services.

Why were you invited to hold this celebration? Was there not any other indivuduals?

I really do not know for sure! I believe it was because I have been active in the anti-war movements against the war in Vietnam and also I had been recognized as a leader in religious circles regarding the opposition to some of the things that the United States’ government had done in various countries in helping to bring about or imposing governments on people that were not popular governments. I’m thinking of for example back in 1954, were the US government helped to overthrow the democratically elected government in Guatemala, and of course in your own country in 1953 in overthrowing the Mossadegh government. And I had been active in supporting and being a part of the opposition in that kind of US’s intervention in other countries.

Before travelling to Iran, did you consult with any American officials about this trip? Did you receive any advices or instructions?

They were opposed to my going! And I’m sure if I had spoken to them the invitation would have been withdrawn. Because the Catholic bishops as a group were hoping to send their own president, the president of the Catholic bishops, to Iran to do the Christmas services. And they went to the state department and they did not receive an invitation.

Tell me about the moment that you entered Iran.

Well, it was around 10:30 pm, the time our plane landed. It was a Sunday afternoon I left from Detroit and went to London and from London to Jordan and from there to Tehran. It was a long trip and by the time I got to Tehran it was 10- 10:30 at night. Then we were met at the airport and driven directly to the embassy and were escorted in and met with the student leaders first, then after that they began to bring the hostages in so that we can celebrate the Christmas services.

After your arrival which Iranian officials did you meet in the embassy?

None at that point. I’m not sure who met us in the airport. I think they were drivers for the government and the first people we really met were the students who were in control of the embassy at the time.

So during the whole time that you were in Iran you didn’t meet with any other officials?

The next day when we entered the embassy we spent the whole night and left there in 5 o clock in the morning after celebrating the services for small groups of hostages, one group after another until early morning. Because after each service there was some time to socialize and then the next group would come in. but by the time it was over, it was 5 am. At that point we just went into our hotel. It was all taken care of by the government. Then later in that day we went over to the foreign ministry building. Two US people were also hostages but they escaped to the foreign ministry so we went there and met with them. And also the foreign minister allowed us to come in and visit with the deputy to the ambassador, a man named Bruce Langone because the ambassador himself was not at the time in the country. There was another person with him and they were provided for in the foreign ministry’s building. They were not in the embassy at the time that the embassy was taken over so they let them stay in the foreign ministry.

How was the reception of the Iranian students from your presence?

Well, it was cordial and friendly. Until they told us what they wanted to do and it was for us to be in three different parts at the embassy ground and celebrate separate services for a group of four or five people at a time. Even though we were from different religious backgrounds our plan was to have one celebration with the whole group of hostages. So, we got into a discussion with the students about that. They were insisting on their way and we wanted to do it in our way so we got into an argument. It went back and forth for half an hour to 45 minutes. Finally we said if you are not going to do it our way we will just leave. But then Dr. Coffin said we came all this distance we are not going to leave. So the other two of us accepted to do it. So we did and afterwards we realized it was apparently a concern on the part of the students who were not trained military people and they were not trained on crowd control. So if the whole group was together, there might be one or two that would begin to try to disrupt things. It could have broken down into quite a riot. The students were armed of course but they might not know how to control the crowd. So I think it was a wise precaution on the part of the students to keep us separated with just a small group at a time. And that actually worked out very well, because we had a chance to celebrate the religious service in a more intimate way with just 4 or 5 people. One group I had was only two women. So we had a chance to interact with them. I was happy we did it the way they wanted us to.

In what atmosphere did you meet with the American hostages?

Well, you could tell they were stressed. The first group I met were three young military people, 19 years old or 20 at the most. Actually the other person was there by mistake because he was a business person. He had been in the embassy trying to get a permit or something and just got caught up in the group. He wasn’t really part of the embassy staff in any ways. But once he was there, he was kept. He was calmer than the other three. I am sure part of the stress was the fact that they had not been in contact with one another and this would have been for a period of six or seven weeks. It took place in November 4th and our visit was December 25th so, they had no contact with anybody outside the embassy, they had not heard anything from their families, nothing from the US government, they didn’t have access to the press and they really had a sense that they had been abandoned whereas in the united states it was in the news all the time. But they had no way of knowing that. I think you can imagine that if you are totally out of touch with your family, your friends and everything you are used to, you began to be concerned and you get anxious and nervous. It was very hard for them, especially the ones that had no military training. Because the military people or those who were higher up in the diplomatic part of the government had more expectations of something like that to happen. They were better trained for such situations. But the ones I met were very young and had no expectation of something like this happening. So they were stressful. They said they had not been physically abused, beaten or anything like that. So basically they were in good health and while we get to talking they got more relax and were very grateful to have a chance to visit with somebody. It was just extreme coincidence that I met with one young man, an army sergeant’s parents just before I left in Detroit. When the news came across that I was going to Iran in the US, his family contacted me and his parents came over to my mother’s house where I went before I left. We sat and visited for half hour to forty five minutes. So I was able to say to him: I just met with your parents just before I left, less than 24 hours and they expressed their concern and love. That meant a lot to him that I could bring that personal message. So, things like that happened that made it a very worthwhile visit.

How the Christmas celebration was held with the embassy employees?

Well, the first thing we did was to introduce ourselves. I told them who I was and then they each introduced himself/herself and then we just carried out some conversations like that. Then I began with their agreement if they wanted to celebrate a Christian liturgy. In the Catholic Church we have what we call the mass and that’s what I celebrated with them. That took 45 minutes or so and they were very grateful for that. Afterwards they were allowed to stay for 20 minutes. There were refreshments, soda and candy. So we just talked for a while and then they were taken out the room and the next people came in.

Did you bring any specific accessories with yourself from US for the Christmas celebration?

No it was all decorated by the ones in charge. They have already decorated the room and there were tables with snacks and cans and bottles of pop and soda. It was all done by the young people who had taken over the embassy. They tried to make it seem like a Christmas celebration. I think it was a nice attempt on their part. Of course when you are being held hostage and you can’t call your parents and wish them a happy Christmas, it still is a good deal. Even though they were all Muslim of course, they attempted to allow the Christians to experience something of what they were used to at charismas.

How long did you stay in Iran?

We got in there in late Monday and Christmas was on Tuesday. I think we probably stayed till Friday. We spent two days in Tehran and were shown various places and sights in the city. We also met with a group of religious leaders at one point for a couple of hours to talk about religion and what was going on and how we needed to work together to bring a resolution to the crisis and to bring peace into the whole situation.

Did you ever get a chance to meet with the US embassy employees after their release?

I met with a couple of them. The young man from Detroit, he was not an embassy employee, he was military and had the duty of a guard in there. Then also I met with one of the women hostages, Kathryn Koob who lived in Iowa and I went out there to do a celebration at one point.

I think she is one of the peace activists in the US right now.

Yes, She has been over the years. I have kind of lost contact with her and haven’t heard anything about her recently but I would see something about her in the paper. The other woman Anne Swift, who was an embassy employee, died later on of an accident. She was horseback riding and somehow fell off the horse and was killed. So I heard about her. And Joe Subic, the young man from the Detroit area, when he was going to celebrate his wedding he wanted me to do the service so I kept up with him in that way. When I got home I called the families of everyone I visited in this trip to tell them what had happened and how the young persons was and how were the things going and brought that kind of a message back for their families.

The presence of Iran’s deposed Shah, Mohammadreza Pahlavi in US was potentially one of the main reasons of the capturing of the US embassy in Iran. To what extent did American people have an understanding of this issue?

Not to a large extent. Most people in the United States, even if they had been aware of it at 1953, were not aware that there has been an overthrow of a democratically elected government that had been brought about by the US government. So they weren’t really aware of that. Until all this came into the news, Iran was not in the news very much. Most people inside US did not know that the shah was put in place as a leader of Iran and his family the Pahlavi family. So after the overthrow in 1979 most people did not know that he was imposed upon the Persian people. That he really wasn’t a Persian family himself and people in US did not know the truth about what was happening in Iran and that his family was closely associated with a lot of corruption. People of Iran were suffering. So the whole situation over the years from 1953 until 1979, twenty something years, there was a lot of underlying unhappiness and dissatisfaction with what was going on and eventually added up to build a revolution, which did happen of course and brought about the overthrow of Shah and he fled. So the people of the US weren’t aware that he is being protected outside the country instead of being returned for a trial.

The Shah tried to go to so many European countries but none of them allowed him to enter. United States was the only country that Shah Pahlavi had received this permission from.

Yes but then he developed cancer and so then he did go to Mexico for a while and short time then he went to Egypt and I think that’s where he died. But the fact that he was allowed to come into the US and people of the US thought it was a merciful thing to do, not because we wanted to protect him. But then it became very unpopular for him to stay in the US also. And that’s why finally he did leave and went to Egypt ultimately.

The August 19th coup resulted in the collapse of Mohammad Mossadegh’s legal government. It is assumed by many Iranian intellectuals that this event resulted in an explicit downturn of democracy in Iran. What have American peace-seeking figures, such as yourself, done to restore the image of the US in Iran?

Not nearly enough. Again the general populations in the US simply don’t know the history. There are a sizable number of people that do know and understand, there are books that have been written about it, explaining the whole thing about the overthrow and what happened afterwards, the repression and so on and about the Pahlavi family. But that’s not taught in our high schools or colleges for kids that take history courses. They usually don’t get that kind of information unless it’s a very selective course in certain places and colleges. The whole story of what happened Iran is not well known in the US which is very sad.

People of Iran have no animosity to hold against American people. What are your suggestions for rapprochement and development of peace between the people of the two countries?

Well, the best thing would be if we can have some exchanges. At the present time I don’t think either government is really ready to do that. It’s sad. If we can have people travel to Iran and see what is going on over there, if Iranian people could come US, not just for business purposes but for cultural purposes, and if we got to know one another it would be very different. We might begin to have a high respect for the culture and the history of Iran. It’s a very ancient country. The history and the culture goes way back than the United States’. We’re about 250 years old, but a country like Iran, you know, your roots go back to thousands of years. Iran has a marvelous and beautiful culture, art and music and way back in ancient histories Cyrus freed the Jews when they were in exile. Cyrus was a Persian who brought the Israelis back to their own land. Most people don’t know that. Even In some ways our religious background is connected.

In the most critical and acute political situations you travelled to Tehran. Why didn’t you continue this path?

Because it is not permitted.

It could have been tried because there have been delegations from different backgrounds that have travelled to Iran.

Well, yeah that’s true, other people have done it. Well, I guess my concerns got diversified way too much, way too soon, because I was still very active in the peace movement in the United States and to abolish nuclear weapons and that has been a major cause for me for decades now. Back in the late 1970s when the treaties where being negotiated and then the start treaties on nuclear weapons, I was very much involved in the peace movements and so did not stay as much in contact with the situation between the US and Iran. I got a lot more involved in the 1980s with what was going on in our own hemisphere and Central America, where the United States tried to overthrow the Nicaraguan government, where it had overthrown the government in Guatemala, supported the very rigid and repressive government in El Salvador. They were closer and seemed in some ways more urgent at the time. Although the underlying urgency of our relationship with Iran is still there and now that you bring it up, I probably should find some more ways to keep more connected.

You are one of the founding members and past president of Pax Christi movement in US. In which year was this foundation established and what main objectives was it established to serve?

We started what we called Pax Christi USA at 1972. The Pax Christi is an international movement and started in Europe immediately after the World War II, As a movement to bring about reconciliation among the European nations which in western Europe all claimed to be Christian nations and yet had been going to war against each other for over hundreds of years! So Pax Christi was an attempt to say we should reunite and reconcile at least on the basis of our religious commitment. If we all follow the same Christ then we ought not to be killing each other, so that was a movement in Europe first and then that kind of thinking and that kind of attitude helped to bring about what we now know as European union and I think it has maintained the peace in Europe itself ever since world war II. Then Pax Christi began to spread outside of Europe. It started in 1945 in Europe but then by the late 60s into the 70s it began to spread to other parts of the world. So it has been between 40 to 50 years now that we have had Pax Christi USA. It still has the same purpose and that is to bring about reconciliation among nations to end war ultimately. Pax Christi has been very much in the forefront of that effort.

During your career as a bishop you have always managed to carry out your peaceful activities. When were you first interested in peaceful and civil activities? What was the very first peace seeking activity you contributed in?

That started in the late 60s. I was ordained a bishop in 1968. Before that I studied in Europe from 1961 to 1964 and when I came back to United States after my studies, the civil rights movements was very active. It was getting very strong, trying to bring about freedom for black people in this country. So I got engaged in that but then also it was in early 60s that we began to send troops over to Vietnam and we illegally, I would say, supported what became a government in South Vietnam. We treated it as though it was a separate country that we supported against the north. When the French were defeated in 54 in Vietnam, there was a two year period were there was to be a time the war would ended and there would be an election in two years for the one country. But the united stated interfered with that and so in 56 instead of an election for the whole country, the country became split and we supported the government of South Vietnam. Throughout the war until 1973 we got out of it and it ended in 1975, but I became very active in the movement against that war as it escalated instead of ending, as President Kennedy would have probably ended it. But under president Johnson it got bigger and bigger and went on for a total of nine years until we finally left. Even after we left we kept an embargo against Vietnam for 25 years but now we finally have more peaceful relations. That was when I really began to get involved with it during that anti Vietnam War period. During that time it was when I helped to start Pax Christi, the catholic peace movement. But it’s just bigger than any particular war. It is trying to rid the world of weapons of mass destruction. That’s why we have the treaties that call for us to disarm and get rid of our nuclear weapons, which we signed the treaties that call for the nonproliferation. But we haven’t lived up to that treaty and so the world is more dangerous place than ever.

Your very first anti-war activities were triggered by your opposition of military presence of the United States in Vietnam. What do you consider to be your main incentive to engage in anti-war activities?

My main incentive and motivation comes out of my religious convictions. God does not intend that we kill our brothers and sisters in war or for any other reason. For the first three centuries or almost four centuries of the Christian era, Christians did not take up arms. They practiced what we call now non-violence in the middle of fourth century. The idea began to be defended that the Christians could engage in war but my incentive and motivation is that we go back to the original Christian stance which was “Christians do not go to war”.

You were among the many activists who overtly expressed your opposition of Iran war. Why did you oppose with the war against Iran?

Because I would be against US going to war against any country!

So, your activities are not specified to Iran, Vietnam…

Well, because that’s where we were at that point doing the greatest damage with war. What we did to the country of Vietnam is really horrific. The way we devastated the countryside with agent orange, the number of Vietnamese people who were killed during that war and the number that is still suffering from the consequences of agent orange, keeps me in that believe that we have to be opposed to all of that. Based on my Christian beliefs we definitely should be opposed to that.

Is your definition of peace and opposition to war restricted to your religious views?

There’s an axiom in Christian teaching that underlying a lot of wars in the world is injustice and the way that the international economic order has worked to keep certain nations oppressed and other nations dominant. And even within nations, even within United States we have unjust situations where there’s an ever bigger gap between the poor and the rich. The system here works in a way that the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. And that happens in an international scale also, and so a lot of my religiously motivated work is to work to bring about justice in the economic order, both in our country and in the international economic order. As we try to build a more just world, it’s much more likely that we can have a peaceful world.

To what extent do you believe that world peace is only reachable through religion?

There are people who are not people of faith who also work very hard for justice so I wouldn’t exclude anyone as a human responsible to try to help fellow human beings to have a just situation and to be able to live in peace. I find my religious convictions motivate me but that’s not the only way to be motivated and to work for justice and peace.

What is your viewpoint about religious extremist groups such as Da’esh which are committing genocide in the name of religion?

Obviously, I would judge that as being totally wrong. And yet religion has been the basis for wars in the past and it’s not something new. We’ve had religious wars. But in every religious group we need to move beyond that misunderstanding of what religion calls for and move towards peaceful living together. One person I met long time ago from Vietnam, a young woman who had been tortured and yet who came out of all of that with a very peaceful spirit and was willing to reconcile with those who have tortured her and I asked her, (she was a Buddhist) , what makes you able to forgive your enemies and I know that’s called for the Christian religion so what makes you do that and forgive and be able to bring yourself to such a peaceful way of living? She said that my conviction is that every religion if you go down to its purest core and basis is the same and calls for us to love one another, not to hate and not kill, but to love. And look at Gandhi as a Hindu, certainly he discovered that in Hinduism and it’s in Islam also. I met with young people in Iraq very committed to reject violence and they were Muslims. There are those in the US that are committed to the same way as the Jewish peace movement that is very strong so I think every religion and just on the basis of our common humanity we should work from that premise that we are here to be our brother or sisters keeper, be there for one another and help all people to come to a realization of peace in their lives.

What aspects of religion are those groups neglecting?

I don’t know really. To me it’s so clear in the Christian scriptures and what Jesus taught and even in the Hebrew Scriptures there’s always a basis for finding a need to love your enemy, to love god first of all but to love your neighbor as yourself. That goes back into Hebrew Scriptures. I’m sure it’s in Islam and Hinduism. Religion should bring us together not take us apart. There’s one God, you know. We have different understanding of god but it is still a God who is love.

There are some beliefs that extremist groups such as ISIS (Daesh) have gained their power by the support of the west. To what extent do you agree with this viewpoint?

Well, I’m not sure I’d say it came only by the west. Maybe they feel oppressed by the west so they are reacting against that. In history you can find that in every religion there has been times for the teachings have been distorted to try to make religion a basis for turning other people into enemies. But I really think that’s a distortion of the true spirit of religion in whatever denomination or religious belief it is, it is distorted to think that your religion calls you to hate.

Due to the racial clashes in Ferguson city, to what extent have you tried to promote peace in America?

Among other things I’d been a pastor in black churches for many years and so I kind of know the situation of black people from their side and I can understand that there has been really repression and oppression of black people in this country. So I have felt highly motivated to try to end racism and oppression of black people in our country. But that’s a long and difficult travel so we still got a long way to go even though the civil rights movement became very prominent and very large movement in this country after World War II and that’s when the racial segregations began to break down. Even though there’s no legal segregations and discrimination, there’s still what we call de facto because besides changing laws you have to change hearts and for people to really learn to love and respect people of another race and culture. It takes some effort and most of all it takes some willingness to get to know other people and help them to know you. So that should really discover your common humanness that makes us brothers and sisters in the human family, regardless of our race or ethnic background.

As a bishop to what extent do you perceive America’s society a religious one?

Superficially, it’s a religious society but I’m not so sure Christianity shapes the minds and attitude of the citizens of the United States. We have on our coins “in God we trust” and yet when God’s teaching say don’t go to war; we trust our weapons more than we trust in God. So it’s not a very good situation. There’s a lot that religious groups have to do to be really true to their religious beliefs so that we can claim ourselves as a religious or even a Christian nation.

How would informing people of their true beliefs could effect America’s foreign policy?

I thought about this last Sunday when I was preaching. If every catholic Christian in United states really should listen deeply to the gospel first of all, and also even to the teachings of Pop john the twenty third, Pop Paul the sixth, Pop John Paul the first and second and now Pop benedict and Pop Francis says….ever since the end of world war II, the catholic church teachings has been to reject war. There are seventy or sixty millions of catholic Christians in this country and we can have a tremendous influence on what our governments did. The president couldn’t reject war by himself even if he was against war, but he needs citizens who are Christians or with whatever religious belief that would act out of those beliefs and insist that that’s the direction that our country should take. But you couldn’t take a huge number of Christian citizens to say no to war. We have a huge job as catholic teachers to try promoting the Christian teachings among our people.

Do you have any plans with any other bishops to travel to Iran in any time in the future?

I don’t have anything imminent but I don’t rule out anything either. If something came along to me that seemed like it could be a good thing to do, I would do it. I would like to travel to Iran as a member of Pax Christi group.